Another trip down my memory lane:

This is the story of an exhibit I did in 1983-86 that toured for 5 years. I wanted to retell it here because it was such a labor of love and I wanted another opportunity to share it with those of you that may not know it. I’ve included some of the images and poems and Lucy Lippard’s essay about the exhibit. All my research papers are now archived at the Valenti Italian Library at the University Library, Seton Hall University, NJ.

The Marietta Robusti Tintoretto Story

Many years ago I was reading a book that was an anthology of women artists when I came upon a couple of paragraphs that told of Marietta Robusti Tintoretto. As people have speculated, it was her name that particularly attracted me to her story but not because it was my name. I was named for my mother and it was because of my mother that the story originally intrigued me. Of course Tintoretto was just one of many women artists whose lives were depicted in the book. Almost all the stories told of struggles, hardships and careers forsaken or overshadowed. But Marietta’s story was emblematic of all the stories. Marietta Tintoretto’s story stuck with me. In 1994 I applied for a grant based on the Tintoretto story to The E.D. Foundation and when they awarded me the grant I devoted the next two years of my work to Marietta’s story.

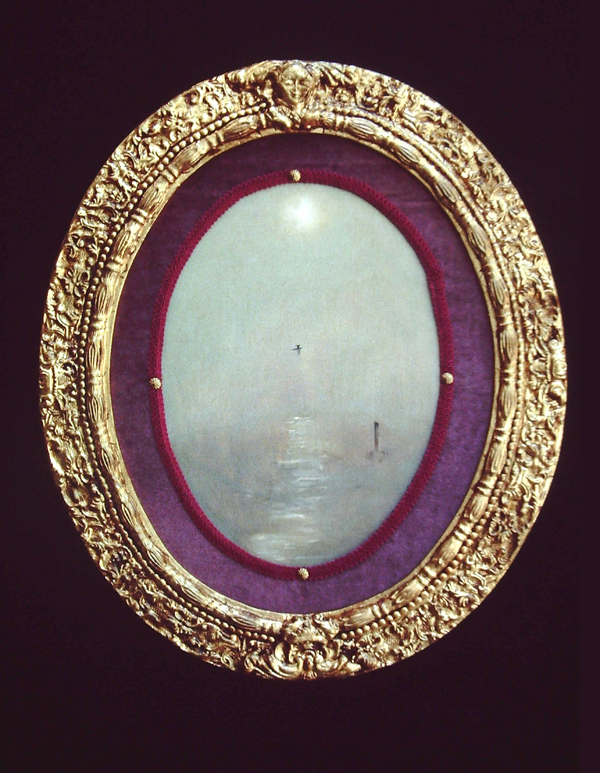

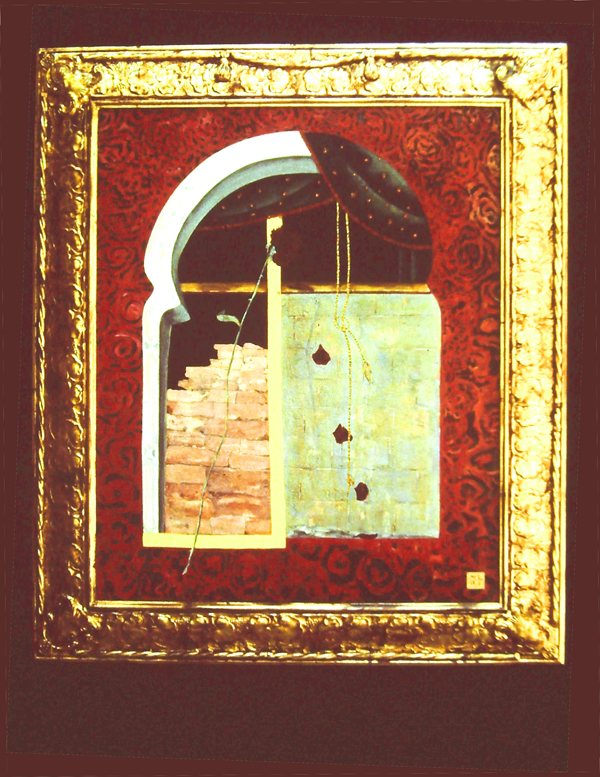

It took some research a good deal of trial and error before I found a format that felt right for the question I was asking which was, “why did women find validation in the arts so difficult to attain?” I addressed this question by focusing on issues that Marietta Tintoretto faced and incorporated those into the paintings. The three largest paintings were the first pieces I completed which are composed of fractured elements because women often get fragmented by their various roles. That fragmentation makes focusing on a career in the arts difficult at best. The elements in these larger paintings take on many guises that, for me, symbolize Venice, the Renaissance and my ideas of Marietta’s life. They are my commentary. The oval paintings of Venice depict the context for the story, a place of much grandeur and love of the arts. Venice had a great influence over the West. It was (and is) an enchanting place that paradoxically harbors dark stories and times.

It took some research a good deal of trial and error before I found a format that felt right for the question I was asking which was, “why did women find validation in the arts so difficult to attain?” I addressed this question by focusing on issues that Marietta Tintoretto faced and incorporated those into the paintings. The three largest paintings were the first pieces I completed which are composed of fractured elements because women often get fragmented by their various roles. That fragmentation makes focusing on a career in the arts difficult at best. The elements in these larger paintings take on many guises that, for me, symbolize Venice, the Renaissance and my ideas of Marietta’s life. They are my commentary. The oval paintings of Venice depict the context for the story, a place of much grandeur and love of the arts. Venice had a great influence over the West. It was (and is) an enchanting place that paradoxically harbors dark stories and times.

The smaller paintings with fabricated frames are like the small formats that so many women artists use. They whisper instead of shout and one must become intimate with them. The frames were constructed of many different media that reminded me of the way some women can seemingly make ‘something from nothing,’ whether it’s dinner or a dress. I used different configurations of the only picture references that I had of the cast, Marietta’s father, Jacopo Tintoretto, Marietta herself and the one painting that is currently attributed to her, Old Man and a Boy, to express different thoughts I had about her story.

The project took a lot of incubating and starts and stops. I discarded some of my early attempts to distill the story to its essence. I had a grand time building the frames with pieces that I cast from molds that I made from some personal, meaningful objects. I loved the oil paint and the luscious colors and derived great pleasure from the gold leafing. I was raised in an ‘old world’ home and the imagery and materials that I used in Marietta’s story seemed familiar. They held both nostalgia and aversion for me. Perhaps the final work retains some of that tension and contradiction.

In this work I want to present the idea that there are many things in our own minds that can stop us, even when the opportunities to fly free present themselves. I use the historical context so women artists can better understand those forces, internally and externally, that both drive and deter them. I have attempted to embody in this work the things that influence us both good and bad. Through telling Marietta’s story, I gained an understanding of my mother’s decision—away from a career in the arts that was so demanding and risky. My intent is to be non judgmental and generous because after all, I am my mother’s child and thus this story is mine as well.

Sons were encouraged

to spread their wings

while daughters, rewarded

for self-inhibition from

childhood, remained as

if in birdcages no matter

how gilded. Because she

was a female prodigy,

Marietta’s destiny was

her father’s creation.

It is difficult to fly free

of a comfortable nest.

–mpl

A Legacy Framed

Commentary by Lucy R. Lippard *

Marietta Leis is reframing the life of Marietta Robusti Tintoretto, who died 400 years ago. She does this literally by making ornate gold frames an integral part of the work; and she does it figuratively, creating a series of metaphors for today’s women artists.

Leis weaves invisible references to her own life with more visible references to that of Marietta Tintoretto. The frames are cast with significant personal belongings, and she was attracted to the Renaissance artist because Marietta was also her mother’s name, and her mother had decided not to seek a career in the arts. Thus, with the aid of a feminist consciousness, a classic 20th-century woman’s story was contrasted with the total support that Tintoretto received from her famous father who dressed her in boy’s clothing, taught her all he knew, and was delighted by her success as a portrait painter. Even as a married woman, she stayed under her father’s roof (and Leis suggests that the father-daughter bonds were so strong that Marietta never found her own voice). Yet no sooner had she died in childbirth at the age of thirty, Tintoretto’s work began to be forgotten, until today scholars definitively attribute only one painting to her.

This is precisely why women artists have to think seriously about “posterity”; it is why Judy Chicago is making such an effort to have her feminist icon—The Dinner Party, permanently housed; it is why so many women artists look anxiously to museums to care for their work. It is, above all, why we know so little about our feminist art history. For centuries women artists’ work has been disappearing, sometimes beneath better-known male names. It is already possible to see the history of the most recent wave of feminist art (beginning in 1969-70) being hidden, forgotten, and rewritten by those who were not there.

This is precisely why women artists have to think seriously about “posterity”; it is why Judy Chicago is making such an effort to have her feminist icon—The Dinner Party, permanently housed; it is why so many women artists look anxiously to museums to care for their work. It is, above all, why we know so little about our feminist art history. For centuries women artists’ work has been disappearing, sometimes beneath better-known male names. It is already possible to see the history of the most recent wave of feminist art (beginning in 1969-70) being hidden, forgotten, and rewritten by those who were not there.

Leis’s exhibition of lyrical, painstaking homages to another Marietta brings these issues to the foreground. At the same time, her works serve as bridges from the sense of formal beauty we inherit from the Italian painting tradition to today’s feminist investigations of opulence and reclamation. Even as their loving detail makes a point of scale, and their fragmentation makes a point of history, the very weight of these small works belie their size. They join Chicago’s Great Ladies, May Steven’s monumental Artemesia Gentileschi, and Miriam Schapiro’s homages to Mary Cassatt and other foremothers to whom all feminists must pledge memory, lest our contemporaries also be lost. These elegant frames protect both the art of Marietta Tintoretto and the art of Marietta Leis.

* Written for the brochure for the exhibition Excerpts from the series: The Marietta Robusti Tintoretto Story at the Jonson Gallery of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

The Marietta Robusti Tintoretti Story (1560-1590)

As told in paintings and text by Marietta Patricia Leis

Marietta Robusti Tintoretto was the exceptionally beautiful daughter of the celebrated Venetian painter, Jacopo Tintoretti. Favoring her above his other children he saw to her education by dressing her as a boy so it would be possible for her to accompany him everywhere. By painting at his side she learned his renowned painting techniques and often did the backgrounds of his works. Entire works originally assigned to her father have since been reattributed to Marietta. Here portraiture also acheived success and she was invited by three royal houses to be their court painter. Marietta refused all offers to leave her father’s house and did not marry until a suitor agreed to live under the elder Tintoretti’s roof. She died one year after the marriage at the age of thirty leaving a grief stricken father whom, some said, never recovered.

Marietta Robusti Tintoretto was the exceptionally beautiful daughter of the celebrated Venetian painter, Jacopo Tintoretti. Favoring her above his other children he saw to her education by dressing her as a boy so it would be possible for her to accompany him everywhere. By painting at his side she learned his renowned painting techniques and often did the backgrounds of his works. Entire works originally assigned to her father have since been reattributed to Marietta. Here portraiture also acheived success and she was invited by three royal houses to be their court painter. Marietta refused all offers to leave her father’s house and did not marry until a suitor agreed to live under the elder Tintoretti’s roof. She died one year after the marriage at the age of thirty leaving a grief stricken father whom, some said, never recovered.

CHOICES

The Renaissance

spoke of freedom and

individuality. But, in

reality, the subjugation

of women remained

unchanged. A woman

either married or entered

the convent—both options

subject to male hierarchy.

So when Marietta

reached a marriageable

age, she too engaged in the

Venetian woman’s arduous

routine of crimping

and bleaching her hair.

Talent and fame do not

immunize a woman from her

socially determined role.

—mpl